James Jamieson, a Technical Specialist at the PSR, talks about what money is, why it matters to payments, and Lord Byron's holiday. This is the second blog in a series of blogs considering different aspects of payments now and in the future.

Here’s a brainteaser for you: who paid for Lord Byron's holiday?

Before we go any further, some of you may be wondering (a) who is Lord Byron, and (b) what does he have to do with money?

I’ll take those in order…

Lord Byron was a poet and scandalous member of the aristocracy in the early 1800s who travelled across Europe.

And second, to fund his fun and frolics – and there were many – he apparently wrote notes promising to pay people at a later point: effectively a lot of IOUs. And that’s going to be the focus of this blog.

Presumably he was expecting those IOUs to be cashed in at some point to his bank in London. But legend has it that this isn't quite what happened…

Those who had the IOUs traded them in exchange for other goods. And – such was his fame – the IOUs kept getting traded. It was as if Byron's IOUs had become cash (albeit privately issued). Incredibly, it’s thought that many of these IOUs were still circulating years later.[1]

So, it raises an interesting question for economists and those in the payments community: who paid for Lord Byron's holiday?

Now, full disclosure: this is a question I was set in an undergraduate economics exam back in my university days. And to be 100% honest I haven't managed to source this story anywhere else, so it appears my economics professor may have latched onto a juicy rumour and turned it into an economics exam puzzler to make an interesting point.

And it seems to have worked, because here I am, a technical specialist at the UK’s economic regulator of payment systems! Seems they had the last laugh after all.

Anyway, back to Byron, the example tells us something important about the money we use today and payments. And it is this: money is a system of trust, most often based around a tradeable debt. And it works as long as everyone trusts the person who stands behind the debts.

Like my old professor, I’m not going to let the truth get in the way of a good anecdote that also serves as a great way to explore the concept of ‘money’.

So here goes.

A brief History of Money

The first known coins to be minted in recognisable form, or ‘money’ to you and I, were invented by the Lydians, who lived in an area that we now think of as western Turkey – and you can see an example of these coins in the British Museum. One forward-thinking Lydian stamped a lump of precious metal with their personal mark. Essentially, they attached their name to the metal, giving it a sense of provenance (and trust) – and we’ll come back to why this mattered in a minute.

The conventional form of public money that we recognise today (i.e., paper money or cash) was invented in ancient China. Money at this point became more like a token representing value than having value in and of itself (unlike the precious metals of the Lydians), and this changed the nature of trust from the one who verified the value of the token, to the one who issued the token, with money taking on more of a tradeable debt characteristic. And you may well know that notes issued by the Bank of England say "I promise to pay the bearer the sum of…" – which helps us all to see cash as a form of debt.

Today, private money, and particularly commercial bank money, is the most abundant form of money and includes deposits held by high street banks (including in your current account). Banks classify it as a debt on their balance sheet. But regardless of whether it is in physical form (as a coin or bank note) or digital (in your bank account or on a digital ledger), public or private, its characteristics remain broadly the same.

The Functions of money

Money has three distinct functions[2]:

- It is a medium of exchange (or means of payment) – When money is used to intermediate the exchange of goods and services, it is performing a function as a medium of exchange.

- It is a unit of account – It is a standard numerical unit of measurement of market value of goods, services, and other transactions. To function as a unit of account, money must be divisible into smaller units without loss of value, fungible (i.e., the pound in my wallet is worth the same as the pound in your wallet) and a specific weight or size to be verifiably countable.

- It is a store of value – To act as a store of value, money must be reliably saved, stored, and retrieved. It must be predictably usable as a medium of exchange when it is retrieved. Additionally, the value of money must remain stable over time.

For something to function as money it will generally need all three characteristics. For example, I might trade a cup of coffee with a neighbour for some green beans they were growing in their back garden. In this transaction, the cup of coffee acts as a medium of exchange, but not a unit of account nor store of value.

For example, if my neighbour wanted to then trade that cup of coffee with someone else, the other person may refuse it either because (i) they don't like coffee, (ii) it's cold (I kept talking to neighbour), or (iii) my neighbour spilt some of it.

So, while almost anything can be used in a payment, not everything can be used as money.

Money relies on trust

It's important to recognise that underpinning the entire concept of money is 'trust'.

When the person being paid (the ‘payee’) receives the money from the person paying (the ‘payer’) they both need to agree what is being used to pay. And they will only agree to use something they mutually trust – that is what makes the whole system work. In ancient times, this was achieved through a stamped coin, giving provenance and ultimately trust in the payment instrument.

Spending and receiving money is based upon 'trust’ and this trust is in the belief that the issuing institution (whether an individual, commercial bank or central bank) can pay what is owed. This is trivial most of the time but is critical in times of crisis.

For example, during the 2007/08 global financial crisis, many consumers lost trust in specific banks. Concerns surrounding whether consumers could withdraw their deposits led to a run on Northern Rock. Ultimately, many banks stopped trusting money markets because they didn't know the credit-worthiness of one another. This lack of trust has led to policy initiatives such as the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, where the first £85k of your savings (deposits) at high street banks are now guaranteed by the scheme. This is on top of the prudential and conduct regulatory regimes applied to Banks in the UK and enhanced since the crisis, all adding layers to trust.

When we move away from well understood concepts such as physical public money (backed by the central bank) and commercial money (bank deposits), we get into some less well understood areas.

- For example, who or what stands behind Bitcoin? The trust mechanism in that and other cryptoassets appears to rely on everyone trusting the system and transactions being recorded in multiple places. Bitcoin does not appear to have the three functions of money as its fluctuations in value means it is not a reliable store of value, although this may just be reflecting the trust system set up around it.

- In cases like stablecoins, which are meant to be backed 1 for 1 with another currency or asset, then the trust is ultimately in the underlying asset (and the regulatory scheme that ensures each stablecoin is backed by the right assets.)

But the question you might be asking right now is how does this relate to payments?

How does this relate to payments?

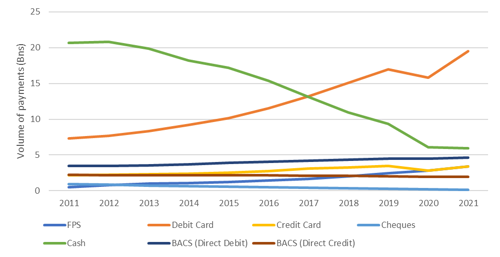

We use money to enable the transfer of funds from one person to another person i.e., making payments. There have been several recent trends which have impacted the types of money we have available. In particular, the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the transition away from cash (i.e., public physical money) towards digital payments and private money.

Source: UK Finance

Whether this shift from public physical money to private digital money is a good thing or not depends on a number of things, including the degree of trust in those who back the debt.

Moving to private money relies on a change of who you trust from the Bank of England who back physical cash, to the individual commercial banks and the whole regulatory regime surrounding private digital money. But the more we rely on private digital money, the greater the importance of payment systems which ultimately move money (and debts) between one private issuer and another – and the regulator that ensures that those systems are developed in a way that considered the interests of all the businesses and consumers that use them, including through promoting competition and innovation in the interests of those users.

What happens if the creation of digital money no longer lies with commercial banks but with either decentralised protocols backed by an underlying asset (stablecoins) or central banks (CBDC)? To what extent would we need existing payment systems?

Moves by existing payment system operators (Visa and Mastercard) into crypto payment chains can be seen as ensuring they will not be bypassed, indicating they will remain relevant. But whereas payments using stablecoins rely on a competing trust network alongside trust in the backing asset and the connection to that asset, a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) changes what or who you need to trust. It changes it from being trust in the ability of the regulatory regime to oversee systematically important banks (and a promise to stand behind retail deposits if that fails), to direct trust in the Bank of England and its ability to stand behind its balance sheet. Are there significant differences between these two approaches? Arguably there shouldn’t be but it is one possible reason why there has been some discussion of limiting the amount that customers can hold in CBDC to prevent the undermining of the current retail banking network.[3]

But regardless of what form of money is being used, the PSR’s role remains critical in ensuring payment systems (whether existing or new ones) are developed in a way that promotes the interest of those who use them, ensuring they are accessible, reliable, secure and value for money.

Incidentally, if you’re interested in digital currencies, in June we published our response to the Treasury and Bank of England’s consultation on the 'digital pound'.

So, who paid for Lord Byron's holiday?

But I know you're all dying to know the answer. So here goes:

On one level, Lord Byron did – he handed over a promise to pay back what he owed (an IOU). Money, as noted above, is just a tradeable debt. Assuming Lord Byron had put some money aside at home for all the IOUs he sent out, so that his reputation as a noble Lord who honoured his debts (or trust) was maintained, he could not use that money on his return.

But there’s a scenario where maybe he didn't pay for it in the end… If everyone accepted the value of the IOU at face value and never cashed them in, then the answer to this question is the people who are the holders of the IOUs today. And so if we assume that Byron effectively created his own private money and no one redeemed the debt – then the poet enjoyed an all-expenses paid holiday to Europe.

All this raises the rather uncomfortable question – one we’ll never know the answer to – if Byron never really intended to pay his debts, and his IOUs were a distraction tactic, should we be adding fraud to his list of scandals?